“All across the world we are noticing growth…. Technology growth is the driving principles that...

06.03.2021

06.03.2021

As widely reported, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Novel Coronavirus (Sars-Cov 2) as a global pandemic on March 11th, 2020. While contagion was the main health impact, government decisions to contain the spread have consequential economic impacts in the short and long terms. China, the second-largest world economy and the purported source of the (Sars-Cov 2) was hard hit and crippled the flow of economic activities within the country. Other bigger economies, including the United States of America (USA), Italy, France, Spain, and Canada have had their own share of the negative economic impact fuelled by the pandemic. The interest, however, in this write-up, is to focus on the developing economic issues caused by the pandemic in Africa, with a major focus on Ghana’s debt management policies and strategies as the country strives to improve public health safety amid a pandemic.

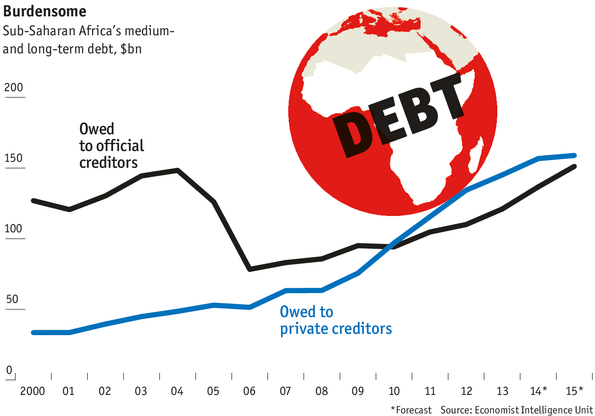

It is documented that developing countries have experienced the largest, fastest, and most broad-based period of debt accumulation in the past 50 years. More critically, the emergence of COVID-19 has caused an increase in public expenditures in health, safety, and social protection, diminished tax revenues, and restricted access to external financing. This situation threatens the economy of Africa and may likely push most African countries into debt distress.

With China as a major trading partner to Africa, most African economies were estimated to experience downward growth rates as there were price drops in major trading commodities such as crude oil, gold, and cocoa. UNCTAD estimated a fall of 1.4% in GDP with 5% public revenue loss for African economies. UNECA also projected a drop of 1.4% in Africa’s GDP. Most African economies faced challenges with responsive policies to mitigate the impacts of the covid-19 on their citizens at risk. Most economies resorted to a reduction in earnings and delivery of monetary aid to citizens and businesses. Some stronger economies injected more cash into the economy to lessen the impacts. Tunisia injected an amount of USD 0.9 million to enhance liquidity. Senegal as well established a “Force Covid-19’’ fund of Euro 2.1 million into the economy while Egypt and Morocco injected USD6.4 billion and USD1 million into their economies to ensure liquidity during the covid-19. In South Africa, an amount of US$160 million was allocated to households and firms at risk with USD8.4 billion funds set aside as risk of redundancy fund and tariff aids for firms with less than USD2.7 million annual turnovers. Some African countries as well-received some stimulus packages to support the strength of their economy. See Table 1 below

***Table 1

| Institution | Policy Response |

| World Bank | US$ 160 billion made accessible to countries until late 2021 |

| African Development Bank (AfDB) | A USD10 billion COVID-19 response package of which USD5.5 billion is set for its sovereign operations in the AfDB countries and USD3.1 billion is operations under the African Development Fund. The Bank also launched a USD3 billion fight COVID-19 social bond which was allocated to central banks and official institutions (53%), Bank treasuries (27%), and asset managers (20%). Notably, 8% of this social bond is set aside for African countries |

| IMF | Africa countries set to receive USD2.7 billion covid-19 emergency fund |

| European Union (EU) | Euro 3.25 billion covid-19 package for African countries |

| Afreximbank | A USD3 billion Pandemic Trade Impact Mitigation Facility (PATIMFA) for covid-19 health and economic impacts in African countries. |

*Stimulus packages by multilateral corporations beneficial to African countries Source: (unctad.org, 2020)

Ghana, COVID-19, and the Fiscal Policies

Ghana which is the second-largest economy in West Africa was already experiencing the turbulent menaces of the covid-19 on its economy. The slowdown of GDP growth, shortfalls in petroleum revenue, the decline in import duties and tax revenues, as well as increased health expenditure, accounted for major macro-fiscal impacts. As part of government efforts to alleviate the financial burdens of the covid-19 pandemic, the central bank, Bank of Ghana (BoG) reduced the policy rate to 14.50% from 16% and reserve rates from 10% to 8% which were announced during the first quarter of 2020. A Coronavirus Alleviation Programme (CAP) of US$219 million from the Stabilization Fund which is 2.5% of the revised GDP. The estimated economic impact is a fiscal gap of 2.9% of revised GDP. Excess money from the Ghana Stabilization Fund was moved into the Contingency Fund to fund the CAP as the limit was reduced from USD300 million to USD100 million (Ken Ofori-Atta, 2020). The BoG has also deferred payment on non-marketable instruments beyond 2022. There was adjusted expenditure on goods and services to the tune of Ghc1,248 million. “The government also secured a World Bank DPO of Ghc1, 716 million and the IMF Rapid Credit Facility to the tune of Ghc3,145 million”. Plans were further advanced to withdraw money from the Ghana Heritage Fund (Ken Ofori-Atta, 2020). These fiscal response policies resulted in a monetary shortfall of “6.6% of revised GDP and a corresponding basic shortfall of 1.1% rebased GDP”.

**The Debt Implications

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as of June 2020, the world economy’s GDP is predicted to shrink by 4.9% in 2020, the largest shrinkage since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The economic toll is greater for advanced economies (AEs), which may shrink by 8.0% throughout the year, especially, the euro area and the UK that may both suffer a 10% reduction in their GDP growth rates. Emerging market economies (EMEs) and developing countries will even face a severe reality as well as their GDP is forecasted to fall by 3.0% due to poor debt sustainability strategies in the midst of coping with the current pandemic.

In the case of Ghana, as at the end of the first quarter of 2020, the country’s gross public debt stock stood at GH¢234.9 billion (US$43.17 billion), signifying 59.30% of rebased GDP. The total debt includes foreign (external) and domestic debt of GH¢124.79 billion (US$22.94 billion) which represents 31.35% of GDP and domestic (internal) debt of GH¢111.26 billion (US$20.49 billion); 27.95 % of GDP. The debt-to-GDP declined from 63.01% to 59.30% mainly due to reduction of the internal debt and the appreciable cedi performance over the US dollar as a result of the decrease in foreign importation and the decrease in demand for the US dollar during the first quarter of 2020 – mainly due to covid-19 economic impacts.

Subsequently, as the government struggled to cushion the shocks of the covid-19, the year 2020 ended with a total public debt of GHC286.9 billion with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 74%. This is the highest figure in nearly four years representing a year-on-year increase of 23.9%. The government’s total spending for 2020 rose by 31.5% against 2019 to a record of Ghc92.2 billion due to covid-19 impacts. At this alarming rate of public debt, there is a higher risk of impeding economic crunch if systematic measures are not taken to sustain the economy. What even makes the debt situation daisy is, in the wake of the covid-19, the government fiscal policies are geared towards spending on consumptions of goods and services rather than infrastructure developmental projects which propel economic development. More critically, should there become a second wave of the pandemic, Ghana’s economy will further be stretched as the government would have to sink deeper into debt to keep the economy robust for a while.

**Policy Implications and Strategies

In the nutshell, since the government may have limited options to internally generate substantive funds to cushion the economic impediments caused by the covid-19, borrowing might be the only available solution, hence, such borrowed funds ought to be efficiently utilized. The government should continue to loosen fiscal policies and accommodate monetary policies as this may spur short-term growth, however, there is a repercussion of an increase in the risks of a deeper financial crisis in the future if well not managed. A two two-pronged approach of shifting fiscal priorities towards expenses with high social payoffs and then promoting fiscal adjustments aimed at a primary surplus and debt resilience can as well be adopted. Thus, Irrespective of the pressure mounted by citizens, private institutions, and NGOs for swift government interventions, the country must strive to focus on investing in self-sustaining sectors to drive economic growth rather than entirely focusing on consumption. Effective monitoring and evaluation to ensure proper execution of projects. With vaccinations for the virus possibly insight, it is time to ponder an effective economic exit strategy into the post-COVID era. These measures would ensure economic effectiveness and prudent management of government resources and as well lessen the economic repercussion of a Post COVID Ghanaian economy.

Be as it may be, there is a need to emphatically state that, there is potential for Ghanaian industries, whether public or private to expand and respond to the demands of goods and services of Ghanaians without necessarily depending on imports. The government can therefore assist these industries (as in the case of 1district, 1factory), especially the small and medium scale enterprises (industries) by removing all unnecessary financial nuisances and legal restrictions that impede their business progress.

As the popular saying goes “Out of debt, out of danger”, hence, it is highly significant for the government of Ghana to extend strict attention to the efficient utilization of debt in order not to throw the economy into financial distress in the next 5-10years.

Dr. Nana Kwame Nkrumah (Ph.D.) is a Post-Doctoral Associate and Chartered Financial Economist. He is the Lead Partner for Tunani Africa-Ghana (A Think right thank), a freelance consultant and corporate trainer with a special interest in development economics, innovation systems, and SME development.

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +233243932107

David Doe Fiergbor is a Business Analyst and a Chartered Economist. He is a personal finance and investment advisor and a business consultant with a special interest in personal financial management and planning, business development, and organizational dynamics management.

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +233249915690

“All across the world we are noticing growth…. Technology growth is the driving principles that...

Expert Opinions …What will COVID-19 do to banking? Perspective from Xavier Vives’s E. N. Kwame...

Business and Financial News Forum on 60 years of Ghana-China relations held….. E. N. Kwame...

Expert Opinions China as an economic bogeyman …..Perspective from Dani Rodrik’s E. N. Kwame Nkrumah...

Business and Financial News IMF: These 3 policies could help Asia’s economic recovery from COVID-19...

Expert Opinions How COVID-19 is making companies act for the long term E. N. Kwame...

©2024. Tunani Africa – Ghana. All Rights Reserved | Designed by XCreativs Technologies