Business and Financial News, Expert Opinions & International News How DeepSeek AI is Disrupting the...

11.07.2020

For the first time in living memory, Asia’s growth is expected to contract by 1.6 percent—a downgrade to the April projection of zero growth. While Asia’s economic growth in the first quarter of 2020 was better than projected in the April World Economic Outlook—partly owing to early stabilization of the virus in some—projections for 2020 have been revised down for most of the countries in the region due to weaker global conditions and more protracted containment measures in several emerging economies.

In the absence of the second wave of infections and with unprecedented policy stimulus to support the recovery, growth in Asia is projected to rebound strongly to 6.6 percent in 2021. But even with this fast pickup in economic activity, output losses due to COVID-19 are likely to persist. We project Asia’s economic output in 2022 to be about 5 percent lower compared with the level predicted before the crisis; and this gap will be much larger if we exclude China, where economic activity has already started to rebound.

Clouds on the horizon

Our projections for 2021 and beyond assume a strong rebound in private demand; however, this may be optimistic for several reasons:

But not all recent developments have been negative. Many Asian countries have been able to provide significant monetary and fiscal policy support—often in the form of guarantees and loans to households and firms. And lower oil prices and improved market sentiment and financial conditions are helping the recovery. However, these factors may not last. For example, our recent update on global financial stability cautions that a sharp adjustment in financial conditions—correcting the current disconnect between financial markets and other parts of the economy—could exacerbate already high borrowing costs for many Asian frontier markets and low-income countries, notably Pacific island countries.

Policies for the recovery

Asian countries are experimenting re-opening, and policies must be geared toward supporting the nascent recovery without exacerbating vulnerabilities. They must use fiscal stimulus wisely and complement it with economic reforms. The priorities include:

Close coordination between monetary and fiscal policy. Monetary policy should help ensure the flow of credit to households and business. Countries facing higher fiscal constraints could also use the central bank’s balance sheet more flexibly, aggressively, and transparently to support bank lending to smaller firms. In the face of large outflows, balance sheet mismatches and limited scope for macroeconomic policy maneuver, temporary capital outflow measures may be needed.

Resource reallocation. A robust recovery hinges on exiting the current phase of support and transitioning to new policies that help ensure resources are reallocated appropriately beyond the initial focus on preventing bankruptcies of incumbent firms, and thereby strengthen the solvency of firms. For example, flattening the bankruptcy curve by streamlining the restructuring and insolvency frameworks; ensuring that banks are adequately capitalized; and facilitating equity injections into viable firms and risk capital for new firms.

Addressing inequalities. Access to health and basic services, finance, and the digital economy should be broadened. Social safety nets should be expanded to extend unemployment insurance coverage to informal workers. Addressing pervasive informality will also require comprehensive labor and product market reforms to improve the business environment and removing onerous legal and regulatory obstacles (especially for startups), and policies to rationale the tax system.

IMF support

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the IMF has offered policy advice, financial assistance, and other support—including virtual initiatives to enhance skills and develop capacity among government officials—to all its member countries. To date, the Fund has provided emergency support to 7 countries across the Asia-Pacific region, with others expressing interest in our emergency financing instruments. Given the large and looming uncertainties at this moment, countries with sound fundamentals may want also to consider use of the Fund’s precautionary credit lines such as the Flexible Credit Line and the Short-Term Liquidity Line to insure against an abrupt tightening in external liquidity. Indeed, S&P Global and Fitch have both published notes stating that facilities like the Fund’s precautionary credit lines could, by cushioning economies, support ratings.

ShareLicense and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.Written by

Chang Yong Rhee, Director, IMF’s Asia and Pacific Department

This article is published in collaboration with IMF Blog.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum

Business and Financial News, Expert Opinions & International News How DeepSeek AI is Disrupting the...

Expert Opinions & Politics and Governance The Re-Election of President Mahama: Implications and Future Prospects...

Expert Opinions & Politics and Governance “From Tradition to Transformation: Uncovering the Dynamic Innovations of...

Expert Opinions Africa’s Prosperity and Population Growth: A Statistical and Business Case Perspective E. N....

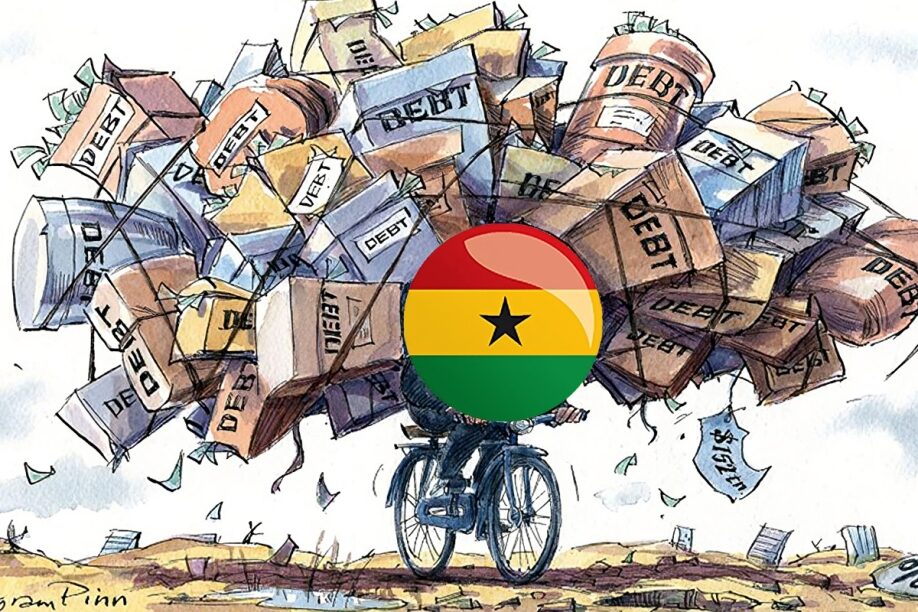

Business and Financial News, Expert Opinions & Politics and Governance Ghana’s decades of darkness: Finance...

Business and Financial News & Expert Opinions Taxation vs. Debt: Is Ghana making the Right...

©2024. Tunani Africa – Ghana. All Rights Reserved | Designed by XCreativs Technologies